How AI is Changing (and Not Changing) the Way I Teach Writing

By Jeanine BencaFeb. 2, 2024 More than anything else, the arrival of high-tech chatbots has inspired me to reclaim the basics: №2 pencils, loose-leaf paper, and — for some lucky students — vintage scratch-&-sniff stickers

When, near the end of 2022, something called “ChatGPT” entered the public consciousness with all the grace of a middle-school fart joke, educators responded by declaring an immediate state of emergency.

It’s “The End of High School English,” Daniel Herman, faculty associate at Bard College’s Institute for Writing and Thinking, prophesied in an oft-cited piece for The Atlantic.

“What winter of 2020 was for COVID-19, winter of 2023 is for ChatGPT,” Jeremy Weissman quipped in the equally apocalyptic “ChatGPT Is A Plague Upon Education.”

Old Testament-inspired headlines notwithstanding, the concerns seemed justified. Especially once students started confirming them.

Last May, an essay appeared in the Chronicles of Higher Education under the headline, “I’m a Student. You have No Idea How Much We’re Using ChatGPT.” In his piece — clearly intended to bitch-slap Boomers out of their latest fog of willful denial — Columbia University undergraduate Owen Kichizo Terry described the ease at which his peers “use AI to do the lion’s share of the thinking while still submitting work that looks like [their] own.”

My own suspicions on this front had already been mounting: I couldn’t mention ChatGPT around students without them “looking sus,’” (to borrow their parlance). I knew I should be hyperventilating. And yet … something was telling me to breathe. I recalled another time in recent memory when lots of smart people prematurely declared that classrooms as we knew them were over.

In early 2020, tens of millions of students retreated online — arguably the largest forced educational experiment in human history. Interestingly, even after Covid receded, virtual school enrollment continued to climb, a trend which investors hailed as the dawn of a new era. Indeed, the global online education market size — evaluated at nearly $217 billion in 2022 — is expected to reach $475 billion by 2030, driven by the anticipated large-scale application of AI and VR classrooms in the coming years. K-12 schools are slated to dominate the surge, according to the global market research company Facts & Factors.

Yet, my own experience as a private reading and writing enrichment instructor in the Bay Area tells a more nuanced story.

Prior to Covid, I never taught online. When the pandemic hit, I quickly shifted all my group ELA classes to Zoom. Though the superiority of in-person classes was immediately clear to me, my expectation was that many families would opt to keep their kids’ classes online even after the quarantine ended. I reasoned they had gotten accustomed to the convenience of not having to drive to my site.

Instead, the opposite proved true. Parents, including Silicon Valley tech professionals working at the forefront of the digital transformation, were desperate for their kids to resume face-to-face instruction.

“You offer in-person classes, right? I really want in-person,” remains the most common post-pandemic query I receive.

In hindsight, and as a mother myself, I should have seen this coming. Parents, if given the choice, will ALWAYS opt for the plan that involves getting their kids the hell out of the house. Duh!

But something else was compelling them, too. And though it probably doesn’t take a child psychiatrist to explain it, my bestie of 30 years, Funda Bachini, MD, happens to be the current Division Chief of Psychiatry at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. “I cannot overstate the power of connection. Actual, in person, connection,” she posted on LinkedIn last year, in response to the United States Surgeon General’s Advisory on the growing public health crisis of isolation and loneliness. “The neurobiology of sitting with someone is different than online or virtual interaction. We are hard-wired to connect. It is essential for our health — mental and physical,” Bachini wrote.

I still recall the day I resumed in-person classes after more than a year of seeing my students only through screens. They had all gotten taller. They were subdued at first, behind their disposable surgical masks. But by the end of the week, they were back to poking each other and pawing the paperbacks on my bookcase. My office once again smelled like Cheetos and questionable adolescent showering habits. And I felt like a fox returning to the forest after years in a wildlife refuge. “Ahh, yes. This is Real Life.”

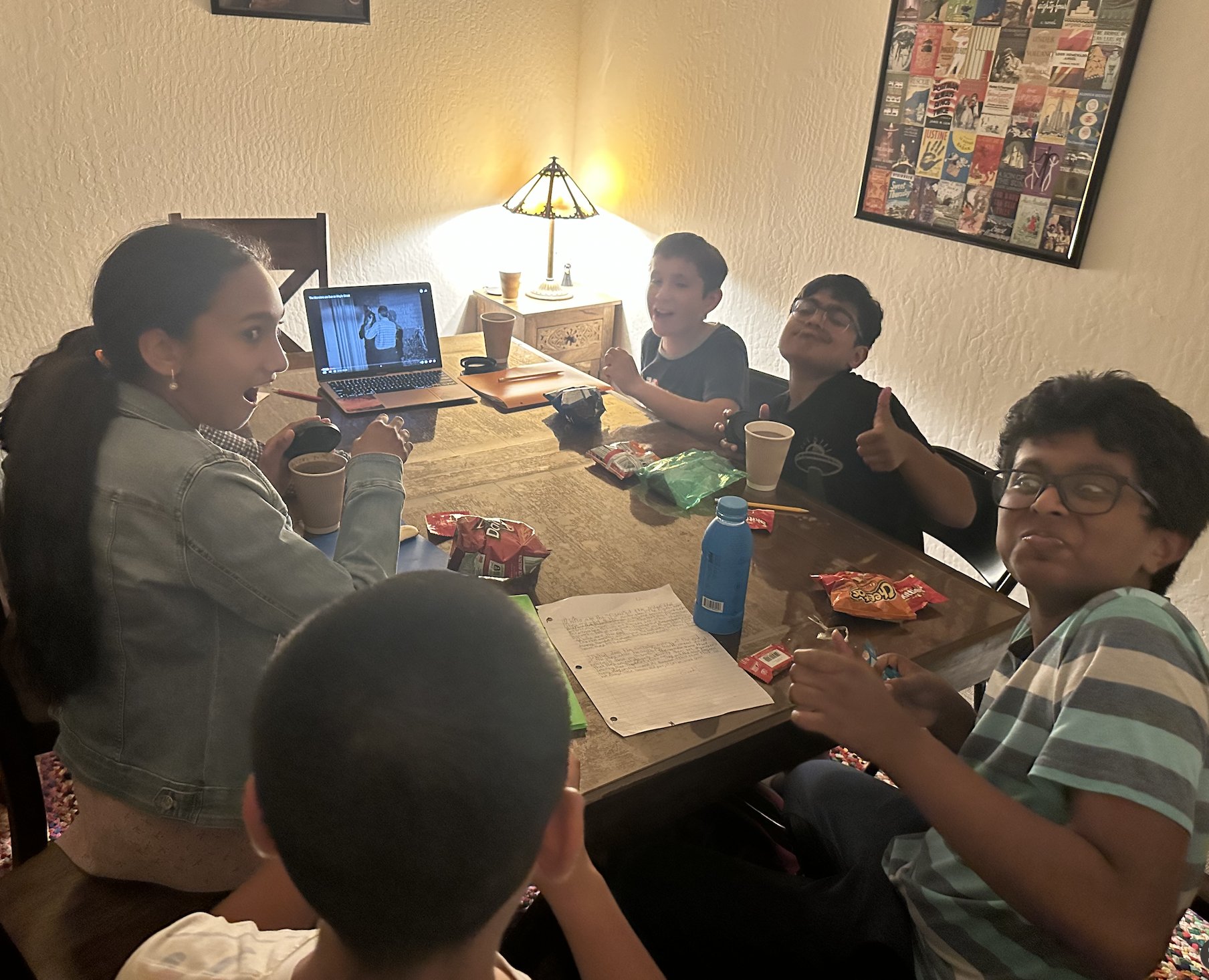

The benefits of Real Life were reaffirmed on a rainy evening this past October, when I guided my regular Tuesday class of sixth graders through one of my favorite activities: reading Rod Serling’s script for “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” the classic episode of The Twilight Zone about a suburban neighborhood’s self-destructive response to an alien invasion. We then watched the original 1960 episode together while gorging on Halloween candy and hot chocolate from my Keurig machine. I posed some discussion questions: What if the episode had been written in 2023? Which people in the neighborhood might be scapegoated today?

“The neighbors wouldn’t suspect aliens,” one student said. “They’d blame hackers from Russia or China.”

The following week I had them write their own modern versions of “Maple Street” and act them out in front of the class. The performances were stilted, self-conscious, annoyingly falsetto, incoherently loud, unhinged, and exhilarating — in that order of evolution. Our shouts and laughter intensified, eventually surpassing the decibel limit at which I start getting nervous about my office neighbors. I didn’t rein it in.

As every writer knows, no drug on earth can best the rush of winning over a live audience. Do it once and you’ll chase that buzz your whole life. I discovered it in sixth grade, composing subversive short stories for my Catholic school classmates. Helping my students experience their own writing highs — a state of transcendence achieved by penning something so original that one’s peers stop scrolling and start listening — remains my mission in the Just-Let-ChatGPT-Write-It-For-You era.

Not long after chatbots arrived on the scene, I began hearing rumors of retaliation from high school English instructors: “Ugh, they’re making us do in-class essays so we can’t cheat with ChatGPT. And we have to handwrite them!” my students complained.

Indeed, more than a decade after cursive was phased out of most California schools, the state legislature last year unanimously passed a law mandating the return of handwriting instruction in elementary schools.

The delightfulness of this irony — teachers going old-school in response to high-tech — can’t be overstated. I have eagerly embraced this trend, requiring my students to write their drafts by hand over multiple sittings, collecting them after each class and redistributing them at the start of the next one.

On a recent Sunday morning, I passed out sheets of loose-leaf and freshly sharpened №2 pencils to my eighth-grade writing enrichment class. We were about to start a literary analysis essay. The theme: humans’ abuse of automation and virtual reality technology in Ray Bradbury’s 1950 dystopian short story “The Veldt.”

“Can’t we type?” they whined.

I cleared my throat demonstratively. “You know, back when I was in middle school …”

(Loud groans).

“If we were lucky, we got to type our final drafts. And that was on typewriters, so we couldn’t even delete our mistakes!” I exclaimed.

For the next 30 minutes, they worked more-or-less steadily, save for the occasional “Ms. Jeaniiiiiine, I don’t feel like thinking today ...”

It occurred to me that this same battle has been occurring in classrooms since time immemorial — teachers trying to convince students of the merits of thinking.

One reassuring way to conceptualize ChatGPT is that it’s basically yesteryear’s CliffsNotes on steroids — though we would be fools to deny that the ease at which AI will enable students to outsource their thinking dwarfs anything previous generations of educators have had to contend with.

When they were finished writing, I corrected their essays, praising their insights and offering suggestions for improvement. Then I did something else teachers have been doing since time immemorial: I busted out the stickers.

My sticker collection, curated over the past 10 years, is a sight to behold. I have fuzzies, I have puffies, I have sparklies and googly-eyeds. But my most coveted are the vintage, 1980s scented stickers I buy on eBay for a buck a pop. No one makes them anymore, yet their catnip effect on kids is as strong as it was when Madonna ruled the airwaves.

My students pounced on them, oohing, awing, and clawing their way through the pile.

“Mmmm,” one girl breathed, huffing the irresistible matte surface of a 40-year-old pepperoni pizza scratch-&-sniffer. Ever so delicately, she peeled it from its glossy backing. Then, with the tenderness of a mama bear, she placed it in the top margin of her hand-written essay, right next to her name.

Intoxicating. Tactile. Real.

April 18, 2023

Hello all,

Spring is here, and with it, the fruits of my 12th graders’ labors on their college application essays last Fall.

I won't lie: this was the toughest year yet for college admissions. That is why I could not be prouder of all my talented, diligent, down-to-earth, hilarious, soon-to-be college freshmen - some of whom I have known since they were in 4th grade. We spent six months last year working together to craft application essays that reflected their unique talents, accomplishments, and personal voices.

Their many acceptance letters hail from UC Irvine, Merced, Santa Cruz, Riverside, Davis, and Berkeley-Electrical Engineering and Computer Science .... not to mention Dartmouth College, University of Michigan, American University, Boston University, University of Washington, Penn State University, Georgetown University, Rice University, Rutgers University, Pepperdine University, Cal Poly SLO, California State University, Baylor University, University of Colorado-Boulder, George Washington University, and Temple University.

I would like to share one particularly inspiring thank you note I received from a student recently. It reads, in part:

Hi Jeanine!!!

I originally had my eye on Davis because it was the only UC I could see myself realistically getting into and attending, but after getting rejected and having my world collapse in on itself, I realized that maybe it wasn’t for me . . . But then came March 17th and I was admitted to Irvine for Comparative Literature!!!!!!

I proceeded to fall madly in love with UCI. How can you not? Their anteater mascot has such a quirky backstory, true to the Irvine vibe! I feel so validated it’s unreal, and my ego is sky high, and i’m bound to fall as is the nature of man (AP Lit reference haha), but I've been given an opportunity, so I’ll pursue it! I wouldn’t be here being this happy and a soon-to-be anteater if not for all your support on my PIQs. Thank you for helping me develop them so thoughtfully . . .

Gooooo Class of 2027! Best of luck to everybody,

Jeanine